Should I have a strategy for my team?

There is such a thing as too much strategy, and sometimes, that might lead you to skip defining one for your team. In today's article I share my perspective on how to deal with this dilemma.

We recently discussed this question in one of my Group Mentoring and Coaching sessions, and an exciting exchange ensued.

Recognizing that many of my readers might be grappling with this dilemma, I thought it would be good to elaborate further on it in today's article.

Let's start with a common issue that is commonly present in “big" organizations.

Strategy Fatigue

People working in large-ish organizations, from many hundreds of employees upward, often face the issue I call Strategy Fatigue.

In such organizations, you usually have people, or even entire teams, whose primary role is to work on strategy. Head of Strategy, Chief Strategy Officer, or Strategy Team are common incarnations of this paradigm. More often than not, you'll find people with a background in management consulting from a big consulting firm there.

Though nothing is inherently wrong with such a setup, it can lead to an annoying side-effect: strategy proliferation.

When someone's full-time job is to work on strategy, that's what they'll do, day in and day out.

However, as strategies tend to cover a long time horizon, at least one year, more commonly three to five years, this often creates the dilemma of how to keep the strategy folks busy.

On the one side, Parkinson's law1 causes the amount of work required to produce the company strategy to balloon, often spilling over the work of other teams: requests for information, input, and documentation grow exponentially.

On the other side, multiple layers of strategies are produced, covering a progressively narrow scope: geography-specific strategies, business domain strategies, customer segment strategies, and whatnot.

The worst thing is that, in the most extreme cases, the goal of producing strategies replaces the original goal of helping the company succeed. You could argue it might even prevent the company from succeeding, as time and attention are taken away from more productive activities in favor of supporting the work of producing the strategy.

In such scenarios, it's not unusual for people to grow disillusioned with strategy work in general, to the point of considering the word strategy a synonym for bureaucracy, waste, and burden.

Many leaders try to protect their team from doing any strategy work and refuse to set a plan for their team.

But that's throwing away the baby with the bath water.

It's akin to people becoming fervent anti-agile because someone tried to implement SAFe in their company and failed miserably.

Tools are rarely the problem; how we use them often causes issues. Strategy is not an exception.

Don't blame the sledgehammer if you struggle to hit a nail with it properly.

An entire book has been written on strategies, Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why it Matters, by Richard Rumlet2. My intention is not to give you a summary of that book; you can find plenty online.

I want to focus on how to help you benefit from strategy work if you're operating in a context of Strategy Fatigue.

My recommendation is based on three principles.

Principle 1: You're better off with a strategy than without one

No matter how much your organization has been voiding the word strategy of any meaning of usefulness, refusing to have one for your team on that basis will not make things better. It might satisfy your desire for autonomy as an act of rebellion, but once that thrill fades, you will be the one left managing your team.

A team lacking any formal strategy is a team that is reactive and responds to emerging needs haphazardly. It will not know whether or not it's doing a good or right job, as it will have no clear definition of good and right. Decisions will tend to be very subjective, based on beliefs and preferences, which can lead to an environment lacking purpose and filled with frustration and bike-shedding3.

For you, this will be even worse, as the lack of a formal strategy for your team will constantly require you to be involved in decisions as the tiebreaker, making your life impossible and adding to the overall frustration of the team.

I often say that the primary purpose of a strategy is to allow distributed decision-making at scale. You want your team members to be equipped with enough guidance to make most decisions without you being involved, and those decisions should be moving the team in the right direction.

Without a strategy, it's challenging to achieve that. Not impossible, but difficult.

If you want to increase your chances of building an organization that can move in the right direction with a high degree of autonomy, defining a strategy for your team will help.

Principle 2: Focus trumps coverage

Another common problem with strategies that get in the way of getting the right thing done is that they try to cover every aspect of a business or an area.

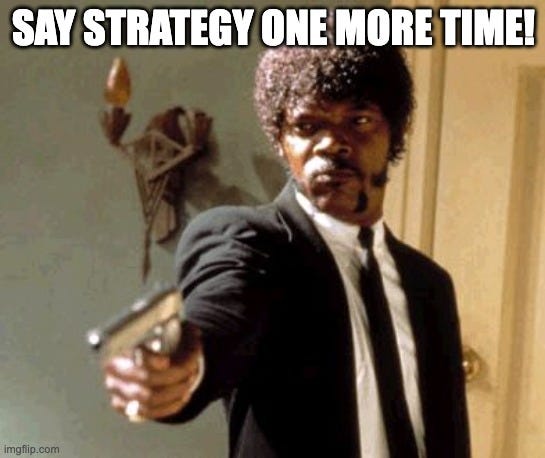

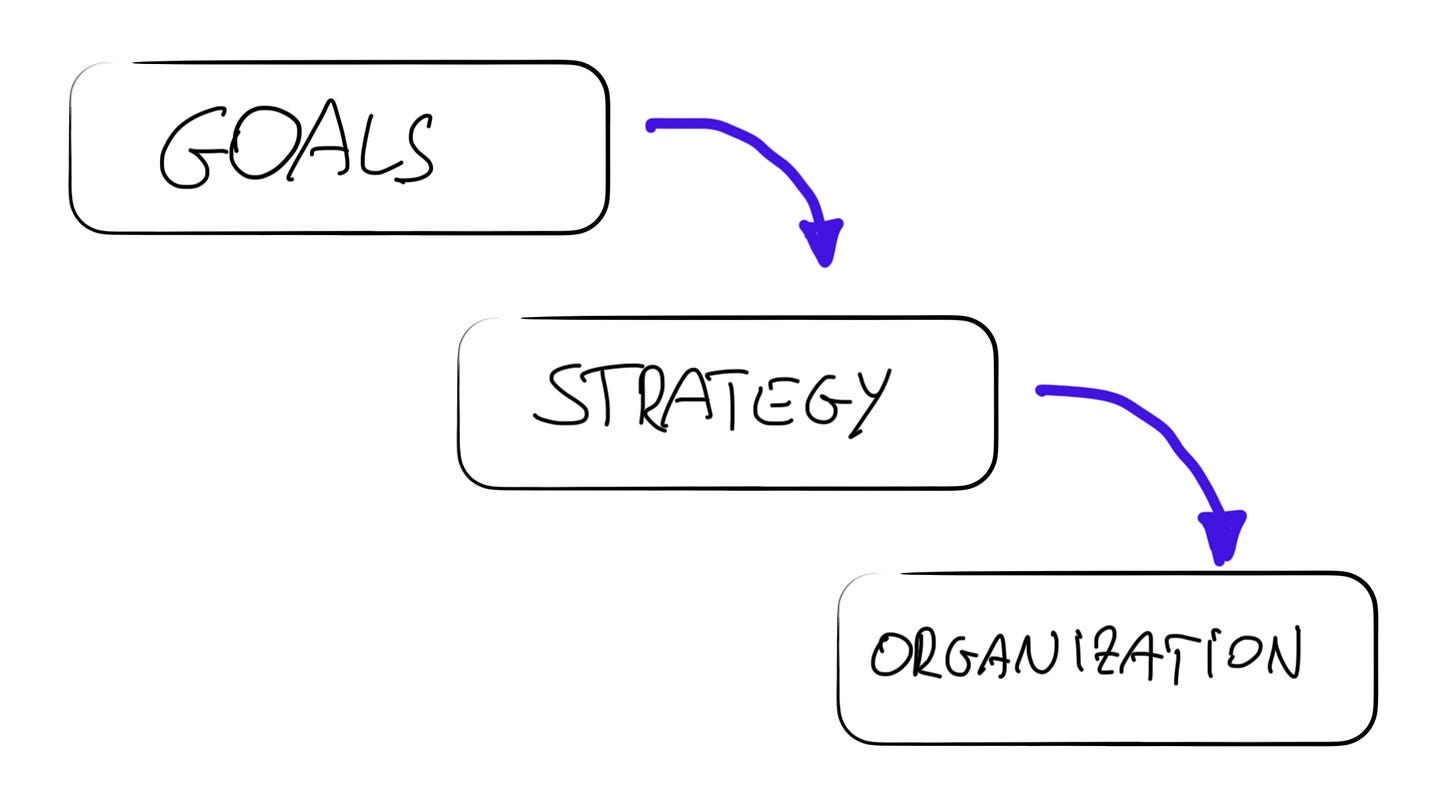

Strategy is part of a hierarchy of decisions and policies that should follow the Goals → Strategy → Organization order:

First, you set your company goals, then the strategy on how you plan to achieve them, and only then do you define the best organizational setup to get there. This is the prescriptive component of a strategy, defining how aspects of the company will have to change or evolve to meet the required goals.

Since challenging the status quo can be daunting and controversial, this is where strategies often fail. They stop trying to be prescriptive and fall back into being descriptive; the organizational setup becomes an input.

A common side effect is that you will end up with a strategy that tries to cover all aspects of the existing organization. If you have a team or business division working on something, it must be reflected in the strategy.

And suddenly, you end up with strategies based on too many focus areas. They don't try to distinguish between what is considered business as usual and what requires unusual time and attention — at the expense of other areas — to allow the company to succeed.

In other words, the strategy, in this case, fails at the goal of prioritization. It tells the organization everything is equally important, and the task of figuring out what to focus on is entirely left to the reader.

This second principle helps you avoid precisely this mistake.

If you're new to this exercise or recovering from PTSD after trying to juggle everything without priorities, I suggest following this straightforward rule: Limit yourself to 3 strategic pillars or areas and prioritize them in order of importance.

Make your goals specific, and avoid trying to include everything you want to happen in the next few months.

Remember, you want to enable distributed decision-making and remove yourself from many discussions. Be specific, and have the courage to sacrifice things that would be nice to have to ensure the essential stuff gets the attention it deserves.

Once you have a first draft of your strategy, I suggest you try the following smoke test.

Submit it to a bunch of people in your team, and without any additional context, ask them to answer the following question:

Does this strategy help you make decisions in your day-to-day job, or does it not?

How people answer is a good indicator of whether your strategy succeeds in prioritizing and focusing people's work.

If not, you know what to do next: review it, cut the non-essential, and repeat the exercise.

Principle 3: Keep it lightweight

Coming up with a formal strategy for your team is hard work. It's not supposed to be easy, as it requires a lot of thinking, discussions, and iterations.

Though there is no way to make hard work easy, we often fall into the trap of making hard work hard to do.

Overcomplicated processes and bureaucracy end up sucking all time and energy, leaving little for the critical thinking necessary to achieve good results.

You can try to make hard work easy to do instead. I addressed this problem in a LinkedIn post a few months ago with slightly different terminology:

Make sure to prioritize answering those critical strategic questions with most of your energy and allocate a smaller amount of it to managing a simple process and documenting the results. It will make it easier to get started, and suddenly, defining a strategy for your team will become a much more tractable task.

You will have plenty of opportunities to improve the process in future iterations.

Don't miss out on a great offer.

If you'd like the chance to discuss such topics with me and fellow practitioners, don't miss out on this great offer for my newsletter readers.

See all the details of the offer in this previous post

At the time of this writing, a few seats are still available on the Founders Plan, but they might run away soon.

If you're still unsure about joining the group, sign up for today's Open Mic session, planned for August 28th, 17.00 CET. Just use the button below to reserve your seat for the session.

I look forward to welcoming you into this new community and helping you navigate your challenges as a leader and practitioner.

See you there!

If you found this valuable

If you found this valuable, here are other ways I can help you and your company:

Follow me on LinkedIn for regular posts on tech leadership throughout the week.

Contact me if you're interested in a Fractional CTO, Technical Advisor, or Board Member for your company.

Work with me 1:1 as your mentor and coach. I love working with driven and competent people in their specific situations and providing personalized guidance, insights, perspectives, and support.

Promote your product or brand to 1,200+ tech leaders from 80+ countries. Just reply to this email to get a conversation started.

For more on Parkinson's law, see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parkinson%27s_law

Another gem from Parkinson; you can find more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_triviality