Two helpful paradoxes, and moving home

Exploring a couple of classic paradoxes that come in handy for navigating today's landscape, and some updates on the future of this newsletter

Today’s issue is a mixed bag of helpful tools to reason about both the present and the future, as well as some important announcements regarding this newsletter.

Let’s start with the helpful bits, and then look at what’s going to happen to this newsletter soon-ish.

We’ll look at two important paradoxes that many people aren’t aware of or prefer to ignore.

Two Key Paradoxes

There are two paradoxes that I’m particularly fond of.

First of all, because like all paradoxes, they stretch our minds and pre-conceived beliefs. Secondly, because these two are highly relevant to much of the public discourse about the impact of technology in various areas of our lives, particularly in productivity at work.

These are Solow’s and Jevons’ paradoxes. Let's start with the first one.

Solow Paradox

This one is more commonly referred to as the Productivity Paradox1, and it takes its origin from a formulation from the Nobel laureate2 and economist Robert Solow, which first appeared on the pages of The New York Times:

You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.3

This original statement was later elaborated into a paper published by Erik Brynjolfsson under the curious title of The Productivity Paradox.

In it, Brynjolfsson went on to illustrate the absence of evidence of impact on productivity despite the massive investments in IT during the 70s and 80s.

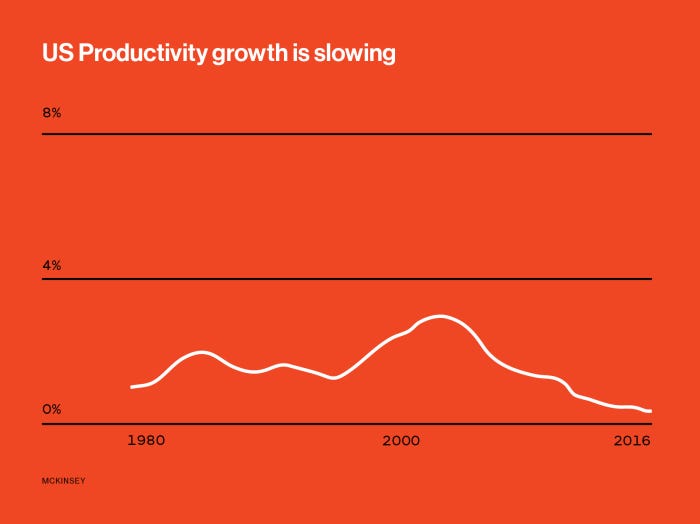

While the following decade of the 90s saw a massive growth in worldwide, and particularly US productivity, as if trying to disprove Brynjolfsson's theory, the same bizarre phenomenon took place again in the period going from 2004 to 2020. Below is a telling chart:

When thinking about this apparent paradox, it is helpful to remember that the absence of evidence must not be confused with evidence of absence.

That is to say that the fact that there is no evidence supporting a certain belief or statement, that's not a sufficient argument to prove such a belief or statement wrong.

That’s a close relative of the common confusion between correlation and causation, which I'm assuming many readers are familiar with.

Many smart people went on to develop explanations to either prove or disprove the productivity paradox, and today it cannot be considered a law. Yet, it keeps poking holes into the often oversimplified narrative that such investments will necessarily lead to improvements in productivity.

For us, dealing with technological investments almost daily, I believe it’s a helpful tool to sharpen our ability to reason about them.

In particular:

How are we measuring the desired outcome? i.e., what’s even a good - if not the right - metric of productivity?4

Not all efficiencies are born equal. Echoing the famous predicament from Goldratt’s theory of constraint, any improvements made on a resource that is not a bottleneck lead to either neutral or even negative results.

We need to think in systems. Reasoning about individual components rarely helps with understanding or achieving significant productivity improvements. For example, the introduction of emails and instant messages has made us all a lot busier, but it’s hard to attribute a significant improvement in productivity to such socio-technical innovation.

With complex and general-purpose technological advancements, the actually measurable results can lag decades. This is actually one of the main interpretations of the Solow paradox, and seems to be in line with many historical perspectives on the impact of the industrial revolution.

The Solow/Productivity paradox is closely linked to another one, which has become quite popular recently as a reaction to many bold statements about AI replacing all software engineers on a reasonably near horizon.

Please let me introduce the Jevons Paradox.

Jevons Paradox

I lost count of how many times Simon Wardley has mentioned Jevons Paradox in recent months, but it’s a lot.5

In its basic form, this paradox can be expressed as follows6:

Contrary to common belief, making a resource more efficient may lead to higher demand and therefore increase its overall consumption.

This observation was first made by William Jevons, an English economist, in 1865.

He made the surprising observation that technological improvements increasing the efficiency of coal use through the Watt steam engine led to an overall increase in coal consumption across the industry!

He concluded that, contrary to commonly held beliefs, technical progress could not be relied upon to reduce fuel consumption.

As is the case for Solow's cousing, Jevons Paradox is not to be intended as an absolute law of economics.

Beware when anyone is trying to sell you that line of thought.

Its helpfulness is in that it helps us apply a good dose of critical thinking when facing blatant oversimplifications that on the surface might sound intuitive or easy to buy into.

Obvious things might turn out not to be if you take the time to dig below the surface.

As an example, for years now, we’ve been hearing that the efficiency improvements in programming made possible by the introduction of LLM-based AI-assisted programming tools will dramatically reduce the demand for software engineers.

Some go as far as to say that there won’t be software engineer jobs anymore very very very soon7. For the sake of this argument, I’ll ignore the fact that actual and measurable efficiency improvements are still largely unproven beyond anecdotal examples and marketing material8, and just assume that they are there, proven, significant, inevitable, here to stay, and <add here your enthusiastic comment about how grateful we should be to be living in these times>.

What the Jevons paradox helps us realize is that it’s not obvious, inevitable, or straightforward that such theoretical improvements in efficiency will lead to a decreased demand for software engineers.

It doesn’t necessarily say the opposite is true either. But it teaches us an important lesson: do not take such seemingly intuitive conclusions for granted. Even more so when people promoting them might reap huge benefits from you believing them.

So, it’s entirely possible, and some folks even believe more likely, that the promised efficiency improvements in generating code will lead to an increased demand for Software Engineers.

Personally, I do tend to believe this interpretation more than the opposite. Based both on the work done by researchers to better understand the Jevons paradox, and on my understanding of both the discipline and market dynamics.

Yet, I’ll be very careful not sell such beliefs as hard and fast predictions.

I generally stay away from predictions, except for easy ones that I can turn into half-serious, half-humoristic articles.

And speaking of predictions, I have one regarding the future of this newsletter. No, I don't expect it to replace all newsletters in the world within six to twelve months.

That would be a tremendous disaster for humanity.

It's about something less disruptive, still pretty radical in its essence.

Moving home

Since the early days of this newsletter, I have made a promise to my readers: that it will stay free forever. I didn’t have any intention to start hiding valuable content behind paywalls.

The good news is that such desire and intention have not changed!

What has changed, and dramatically, since I started publishing is the overall state of the tech industry.

It has increasingly become the armed hand supporting deliberate efforts to undermine the democratic institutions in the US and worldwide.

In the past few months, I’ve engaged in an effort to reduce my dependency on mostly US-based big tech. In January, I turned off photo backup on Google Photos and moved all my family’s pictures over to Immich9, and moved to Helium10 as my default browser.

While I’m waiting for Proton Calendar to offer an integration with Cal.com or offer a native solution for calendar booking, so that I can definitely move out of Google Workspace, I’m now taking aim at Substack.

There are multiple reasons for that.

One is simply that Substack is a Silicon Valley company.

As such, depending on it has become too much of a liability and risk, especially for an EU citizen. The dude who treats geopolitics like price negotiation at the local fish market might impose serious limitations for people like me, and I do not want to be exposed to that risk.

Secondly, Substack has been dealing very poorly with hate speech, white suprematism and nazi-friendly publications11. Though my newsletter is arguably insignificant for Substack’s overall traffic, I don’t want to even remotely contribute to the rise of such ideologies in our current society. I leave that part of the job to the POTUS and his friends.

Finally, Substack as a product has been increasingly drifting towards the generally enshittified experience of social networks with a focus on followers, chats, notes, and similarly irrelevant features, while neglecting its core, such as having reliable deliverability and stats.

When compared with other options, today’s main selling point for Substack is that it’s free (as in beer). I’d rather pay the equivalent of a few beers and focus on an offer that is rooted in free (as in freedom) solutions and human decency12.

Due to all of the above, I intend to move Sudo Make Me a CTO over to Ghost in the upcoming months.

I still have to figure out most of the details, but the decision has been made. By doing that, I’ll be supporting a true OSS project by giving money a non-profit foundation based outside of the US.

The main downside of Ghost is that it comes with a monthly recurring cost, even for free newsletters. That’s reasonable, as there are infrastructure and operational costs involved with hosting the content and shipping thousands of emails each month.

It's either that, or you can self-host it. But I’m not really into self-hosting email-related services in 2025.

This means I’ll need to find a way to cover those costs, which for the current ~10K subscribers would set me back approx $90/month. Overall, not a big deal. But significant enough to convince me to test a slightly different approach.

I will be adding paid tiers, with a twist.

None of them will be required to access all the written content. In other words, no article, present or future, will end up behind a paywall, as that would be against my intentions.

I think about these tiers instead as ways for loyal readers to signal their support. I might add in special perks such as 1to1 sessions for yearly subscriptions or something similar, but the newsletter content will stay free for everyone.

I’ll start with a test for that model right here on Substack, as a way to gauge the viability of the model.

Starting from this issue, you’ll see occasional buttons and links inviting you to upgrade to a supporter-paid plan. I intend to be transparent about the number of people upgrading to paid tier(s), without violating anyone's privacy.

As these things go, the more people who support with a paid subscription, the more time I’ll be able to prioritise newsletter content over other activities.

By becoming a paid subcriber you’ll not only support my work, but make it available for free to people who might not be able to afford to pay for valuable content.

Now, there is an annoying limitation with Substack (one of many).

It imposes a minimum price of €5/month or €50/year for paid plans.

While I intend to make cheaper plans when moving over to Ghost13, this is what we’ll need to start with.

So, if you’ve been enjoying the content and would like to support my work, please consider upgrading to a supporting tier.

If you don’t, you’ll still be able to access all the content as before. No hard feelings :)

Looking forward to seeing the first results of this pre-migration test.

Thanks in advance to all those who will decide to support!

Productivity Paradox Wikipedia page

He actually got the Nobel directly, rather than as a second-hand gift from someone else, as it has become customary in recent history.

Don't get me started on GDP, or lines of code, or percentage of code written by different entities or creatures, etc

For those who like short videos in the annoying vertical format, here is one with him talking exactly about that.

For more details, consult the corresponding Wikipedia page

The latest example has been Dario Amodei at the recent World Rapacious Greed Forum in Davos, stating that SWEs will be replaced within 6 to 12 months. If this statement sounds familiar, it’s because it is. Famously, Eric Schmidt said something similar in April last year. These are all manifestations of what’s often referred to as the “ever-receding horizon of the future”. If you want a fitting example, just look at Musk’s statements about full self-driving being a few months away. I express my profound admiration and gratitude for the folks who took the time to list all of them in a detailed Wikipedia article.

What I find hilarious, though slightly off-topic for today’s article, is an observation I’ve made only recently. The people who today seem to believe in the necessity for people to stop writing code and instead “manage agents”, are largely the same class of people who a couple of years back were beating on a different drum. They were stating boldly that engineering managers and other senior tech leaders should consider writing code as part of their daily duties. According to this cyclothymic narrative, while until recently hands-off management sounded like anathema, it has now become the new definition of a “builder”. The only difference is that instead of a few people leading large groups of other people to achieve that (bad!), now we want every single person to lead large groups of questionably less reliable artificial artifacts (good!). They went from trying to kill management as a discipline to promoting the “new” idea that everyone should now be a manager of inanimate creatures in the space of a few months. George Orwell himself would hardly believe we got to this point.

Immich is one of those great open source projects filling a clear need for self-hosted alternatives to the common cloud-based options. Check it out. While it’s far from perfect, it has everything I need and has been egregiously satisfying my family’s needs so far.

Helium is an OSS browser based on Chromium, with plenty of privacy-by-default additions. It also deliberately avoids any AI-based bloat.

This article from The Atlantic pretty much summarizes the whole issue.

For the young folks here, the free as in beer vs free as in freedom has long been a thing in the FLOSS community.

I'm seriously thinking about going for something around €2-€3 a month, to make it so inconspicuous that it becomes almost a no-brainer. But if plenty of people are willing to pay €5, I might take this as an opportunity to invest significantly more time in making the content better.