Communication Tips for Engineering Leaders

How to overcome common challenges Engineering Leaders face when communicating with their peers and members of the executive team

I'm preparing a communication session for current and aspiring Engineering Leaders. The session will focus on overcoming the everyday challenges they face when communicating with non-tech peers, such as business leaders, members of the executive team, or their managers.

Do you feel like you're navigating your leadership journey alone because your managers are too busy to offer guidance? You're not alone—and there's a better way to grow.

If this resonates with you, my Community Membership might be exactly what you need. You'll get In-Depth Monthly Sessions, Live Q&A, Problem-Solving Sessions, Networking in a community with other leaders facing similar challenges, and access to premium resources!

By the way, I am offering 10 seats with a limited 30% discount + a free 1-1 mentoring session with me until the end of this week!

In a previous article, I focused on the interactions with the executive team1 and the most common challenges I've noticed there.

Today's article will focus on four key areas that have been reported as challenges by a sample of engineering leaders who have been through a specific training program:

Basic communication challenges

Speaking the business language

Inability to influence key stakeholders

Let's explore them one by one.

#1: Basic communication challenges

This is how this first challenge has been shared with me:

Fundamental communication gaps: They don't know how to communicate effectively and struggle to articulate or shape an idea, especially when discussing topics outside their technical expertise.

The solution to this issue is deliberate practice.

In most cases, engineering leaders have spent the best part of their academic and professional careers accumulating technical knowledge, often at the expense of the skills necessary to collaborate effectively with others.

Challenges in expressing and communicating our thoughts are a consequence of two main gaps:

Cognitive gaps: Inability to focus on complex topics for an extended time.

Communication gaps: Inability to translate our thoughts into a language-based representation that other brains can process and understand at a deep level.

The good news is that you can often practice the two simultaneously through deliberate practice.

There is plenty of literature online about deliberate practice so that I won't go into a dissertation about it. Just remember that casually exposing yourself to new concepts and practicing what you already know do not count as deliberate practice.2

Read a lot. Yes, a lot.

Some say there is no difference from a learning perspective between watching a YouTube video and reading a book. I'm afraid I have to disagree and for many reasons. Reading is way more conducive to a state of intense focus. Videos, especially when watched on devices often associated with notifications and distractions, have been proven less effective in fully engaging our brains.3

My recommendation is to establish a reading routine. If possible, favor paper books. Pick interesting subjects, but try to read various styles and topics.

Get into the habit of marking passages that express a concept you want to make yours or parts that are particularly well articulated. Do some good old text analysis regularly, and try to learn from those making communication their profession.

Write your thoughts and ideas down.

You must first be proficient in writing to improve your oral communication skills.

The reason is simple: you can leverage aspects of nonverbal communication when speaking, such as the tone of your voice or facial expressions, but you cannot edit your content. Well, unless you really want to annoy your audience.

When writing, you can allow yourself the luxury of not getting it right at the first take.

Write a first draft. Go back and edit. Reread it. Go back and edit.

Keep doing it until you're satisfied with the form you end up with. Read it aloud, and practice expressing your thoughts using the same words and expressions.

Plan what you're going to say ahead of a meeting.

We often think that preparing for a meeting means knowing the agenda and reading the required pre-read material. In my view, that's necessary but insufficient for an effective meeting, especially a high-stakes one.

For crucial meetings, such as those with the executive team to discuss plans and priorities or one-to-one sessions with your peers or your boss, you should take one more step to become more effective: prepare what you will say and how you will say it.

The best way to do this is by doing what I already suggested: write down your thoughts.

You can do it in an online document or a fleeting note on a piece of paper on your desk. It doesn't matter. What matters is that you invest time up-front preparing your script. Come into the meeting with answers to at least these two questions:

What is your goal for the meeting?

What are the key points you want to get through?

How are you going to present those points?

Do this systematically, and your effectiveness in those conversations will keep growing.

Ask questions to check people's understanding.

The best way to confirm that people understand you is to ask them. The problem, though, is that we often ask the wrong question.

We often ask a binary question like this: Was it clear?

The problem with formulating the question as binary choice is that you'll often get a Yes as an answer, even when people understand something very different.

A better way to check for understanding is to ask them to explain what they understood.

This will initially feel very awkward, but the more you practice it, the more feedback you'll receive on improving your expression.

As a bonus, the more you do it, the more you'll learn about the person in front of you: how they reason, what concepts seem to resonate more or less with them, and what they care about. This information will be essential in helping you communicate in a way that will be understood at the first take, gradually reducing the need for validation.

#2: Speaking the Business Language

The extended formulation of this second category of challenges is the following:

The biggest challenge for engineering leaders in startups is speaking in business terms. This stems from both a lack of business knowledge and clear communication skill deficiencies: understanding the other party, grasping their incentives, aligning those incentives with your own, and being able to express ideas briefly and concisely.

If the language of business is foreign to you, you'll need to do what's required to learn a new idiom.

You must invest your time and energy in developing the new skill while improving your understanding of your firm's business context.

Learn the language of your business.

You will rarely find terms such as microservices, Kafka, or CQRS in the business language.4 You are more likely to find other terms instead, suck as P&L, Bottom Line, Balance Sheet, or NPV.5 You might or may not be familiar with some of this terminology. If you aren't, there are two main ways to fill the gap:

Educate yourself on the topic via online and offline material. You do not need to become an expert unless you discover a sudden passion for finance. You'll need enough understanding of the critical concepts to reason about them, understand their meaning when used in discussions around you, and use them where appropriate.

Ask stupid questions. I've done this often, and you'll be surprised at how happy people are to teach you something. Be careful, though, not taking up too much time in meaningful conversations just for your own sake. You can get creative here and experiment. You might want to take your CFO out for lunch and ask them to give you an introduction to some concepts. This will also have the compound effect of building a rapport with someone you want to influence. More on that later.

There is no single way to learn this new foreign language.

What really matters is deliberate practice — have I mentioned this already?

Understand the overall time horizon for your company.

Different companies operate at various time horizons. You must know the primary time horizon within which your company operates.

If you work for a startup that aims for product-market fit while burning through the first investment round, your time horizon will be defined by when the money runs out based on your current burn rate.

Conversely, if your company is highly profitable and looking to expand its business, it might be operating at the scale of years or even decades.

You need to know this information because your proposals and communication should be relevant to the specific horizon.

You'll hardly find an audience interested in an investment that will pay back in 2-3 years when every one of your peers is laser-focused on getting enough money in to extend the company life span by 12 months.

Demonstrating that you can make sensible trade-offs between short-term ROI and long-term sustainability based on your firm's budget will earn you respect from the executive team.

In other words, a deeper understanding of the operating context will help you leverage flexibility and pragmatism rather than sticking to dogmatic approaches.

Sometimes, deliberately taking on technical debt is the best way to support your business where it is.

Paraphrase to validate your understanding.

This is the inverse of asking questions to validate other people's understanding. Don't wait for people to ask you what you understood, as they might not feel comfortable doing that, or they might assume you got it right.

Take the time to repeat what you have understood in your own words, and ask if you got it right. It's crucial to paraphrase for a few reasons:

You'll process the information in your mind rather than memorize it verbatim. That's understanding 101.

You will help the other person see the same concept through different perspectives, and they might pick some of your language in the future.

It will become more apparent if there is a misunderstanding.

As usual, you must balance using these techniques systematically and not wasting everyone's time.

Use them when the message is crucial, and a misunderstanding could have significant consequences. Do this too often, and it will backfire.

#3: Inability to influence the key stakeholders

Finally, this is how many first-time CTOs feel:

They can't sell their ideas when communicating with their peers and/or managers, who are often CEOs, investors, or other executives. In other words, they lack influence. What typically happens is that, unable to communicate their ideas persuasively and seeing no one buying into them, other people's ideas end up being imposed on them, ultimately harming not just themselves but their entire teams.

The lack of basic communication skills, combined with the power dynamics maintained in high-level structures, create a subjugation of technology teams to other areas due to the communication skills their managers lack.

If I had a Bitcoin for every time I heard about similar frustrations, I'd be the wealthiest person on the planet for a few minutes every four years.

That hasn't happened, so here I am writing for you, my dear readers.

As for the other challenges we explored, there isn't a quick fix for this one. Today's results usually result from our actions and investments years ago. But as the saying goes.

The best moment to plant a tree was 10 years ago.

The next best moment is right now.

It's never too late to start investing in your ability to influence others, but patience is the key here.

Let's examine three areas you can develop to improve your ability to influence your organization's business stakeholders.

Build an image of competence.

This might sound obvious, but is sometimes overlooked.

As someone else would say, if you want people to regard you highly—a necessary condition for influence—you must have your act together.

Having your act together generally boils down to one simple — but not easy — thing: you have a track record of consistently doing what you said you would do.

How to do it specifically is outside of the scope of this article, but it has a lot to do with two things:

How you organize your work. Nobody else will do this on your behalf, so you'd better get on top of your system. I wrote a few articles that I recommend you check out.6

How you communicate progress and unplanned events. Whenever you and your team are working on something, you should proactively communicate progress, surprises, obstacles, and changes in scope. How often you need to do that is highly context-dependent. As a smoke test, you can use the following heuristic: if peers are reaching out to you regularly asking for updates, you're not doing it often — or well — enough.

This area should be the first one you want to focus on to gain credibility.

But be careful about how you do it, as that has to do with another vital lever you might unknowingly use to your disadvantage.

Understand the impact of likability.

I've been reading a lot of literature recently on the impact of likability on how people perceive you. Some studies have reported that likeability can have a significantly higher impact than competence on people's ability to influence others.7

This doesn't mean you should invest all your energy in becoming nice to make up for your incompetence. Don't do that.

The challenge for many technical profiles is more often the opposite.

They over-index on competence and downplay and neglect how likable they appear in their interactions with others. We all know about the archetype of the brilliant jerk, and we should steer clear of it.

Focus on finding ways to make working with you more agreeable.

This can involve making caring for others a part of one's identity, focusing on understanding other people's needs, or simply investing time in building rapport with key stakeholders.

There is a reason why many high-performing executive teams often spend time together outside of work.

It's not just a Machiavellian way of managing power dynamics, nor a sign that they're secretly part of a cult—at least not outside the Silicon Valley bro-culture.

It's a natural way to get to know someone more profoundly, which can improve a working relationship.

Find ways to think and act win-win.

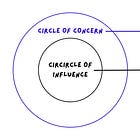

Thinking win-win is one of the seven habits Steven Covey associated with highly effective people.8 It involves finding ways to achieve something that benefits both parties. Thinking and acting this way can unlock massive potential in relationships with executive team members.

It all begins with understanding other people's needs and struggles. Then, find ways to match them with solutions you could provide that would also benefit you in the long term. Adam Grant extensively covers this topic in his book Give and Take9, which I highly recommend.

If you don't want to read the book, the key concept is to find ways to help others in a way that benefits you. This will prevent you from becoming a "taker" — someone who's always trying to take advantage of others for their benefit — or a "giver" — constantly sacrificing their self-interest to serve others.

Do you want to talk about this?

If you'd like to explore this and similar topics further, you can join a group of engineering leaders leveraging my community to accelerate their growth.

Secure one of the ten seats available in the community. Once sold out, sign-up will be closed to allow the new members to settle in before I open additional slots.

The offer will expire at the end of this week, after which the price will increase.

I'm looking forward to seeing you there!

For those interested in a real-life example to understand the difference between passive exposure and deliberate practice, I will share one from my experience learning foreign languages. When I moved to Mexico in early 2013, I didn't speak a single word of Spanish. I initially used English as my favorite working language just to get started, but I quickly decided to move to Spanish.

I remember one day telling my team that from now on, all our meetings will be in Spanish. I'll suck big time for a while until I'll eventually get better. I struggled and kept asking my team members to teach me new words. After about six months, I was speaking, and my Spanish kept improving.

Conversely, when I moved to Barcelona in 2016, I thought I would quickly learn Catalan, given my prior Italian, Spanish, and French knowledge. I took a passive approach and defaulted to speaking only Spanish out of convenience.

Eight years later, I do have a good understanding of the language—which I acquired through passive exposure—but I'm genuinely unable to speak it because I've never really practiced it.

It turns out that even reading on electronic devices seems to be less effective than reading on physical devices. The research is still ongoing, but this is one such area where I'd rather not take the risk of the research turning out to be right. https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/reading-electronic-devices-may-interfere-science-reading-comprehension

Unless your company is in the business of engineering tools, a number that keeps growing as the market matures

In my experience, the sad reality is that companies might talk about NPV but rarely use it to decide whether to invest in an initiative. There are many reasons for this, and I'm sorry, but they won't fit in a footnote.

There are two articles relevant here. The first is a lesson from Richard Feynman, and the second is an overview of my system. Happy reading.